Psychedelic Medicine & Mental Health

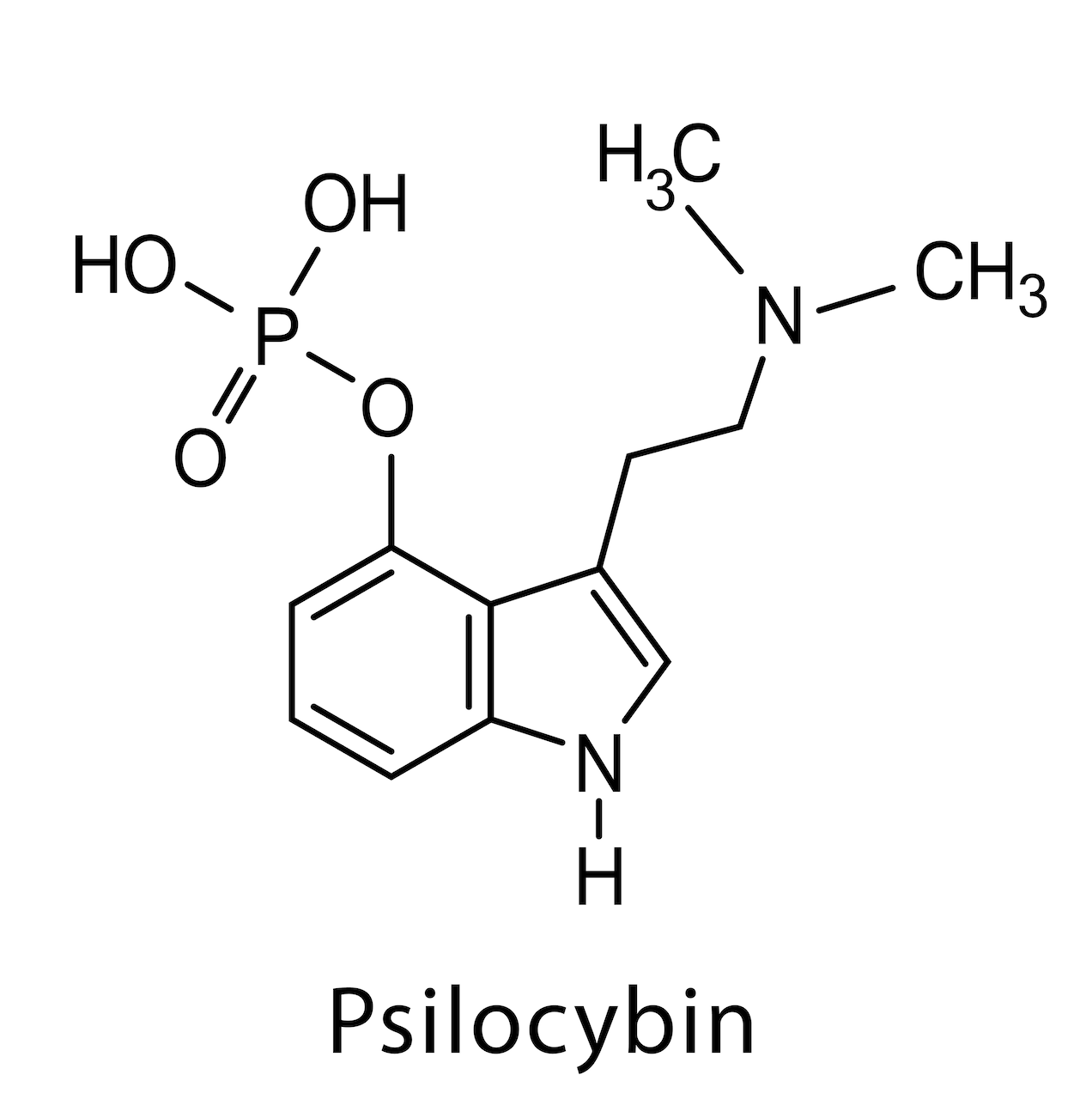

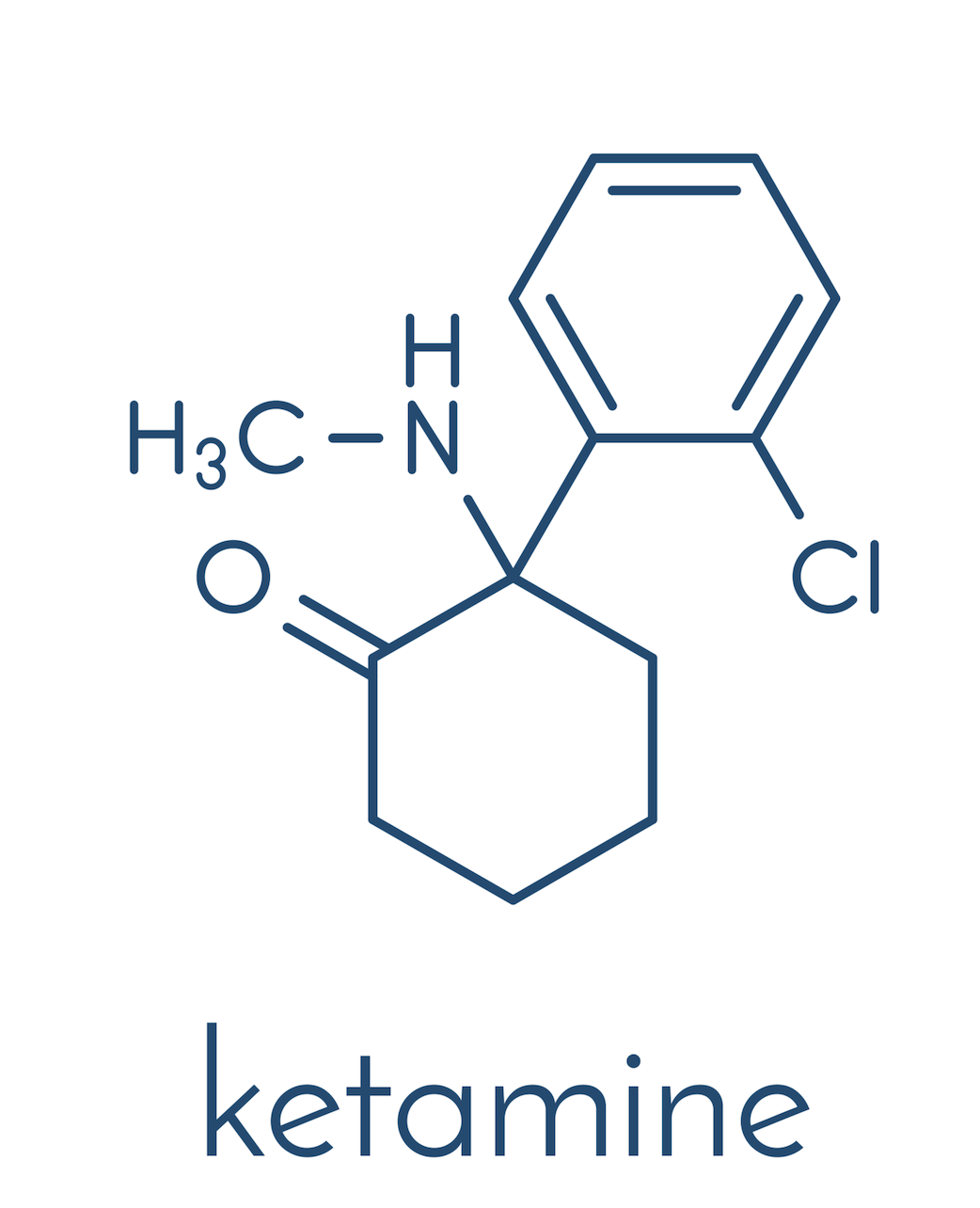

The consequence is mental fatigue, burn-out, stress and depression, until, eventually, physical symptoms surface. Dr. Alexander Bacher, a clinical psychologist and addiction specialist will take us on a brief walk through the world of psychedelic medicine and explain how compounds like psilocybin or MDMA can potentially help us suppress this loop system and re-connect not only with the world around us, but also with our true selves. Disclaimer This website does not provide medical advice. The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images, and other material, contained on this website is for educational purposes only. The purpose of this article is to promote broad consumer understanding and knowledge of various health topics. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health care providers with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment before undertaking a new health care regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website! Dr. Bogner: All right. Welcome back. Today I thought we want to maybe take care of ourselves a little bit, for us parents, for all of us, not only parents affected and their families with autism, but maybe other problems. For me in particular, as a parent of a child with autism, that can cause stress, emotional, financial, and sometimes even physical, because meeting the complex needs of a person with autism can put any family under a great deal of stress. And a lot of these issues that come up are self-blame, and guilt, especially common in families affected with autism, and that can predict worsening depression and lower life satisfaction over time. In fact, a University of California-San Francisco study found that half of moms of kids with autism have high depressive symptoms. I’m not sure why they only mention moms. What about dads? So I guess I hereby identify as a mom. But with that being said, there are other issues that we’re dealing with in regard to life in general. Stress could be PTSD, something that happened to us, an accident or abuse, or any sort of trauma that we have mentally that’s deep in our subconscious and resurfacing without our input. And the conventional methods for many of us just don’t work. Can’t suppress that with pharmaceutical medications. I don’t think that’s helpful. So there are a lot of other remedies that we can explore. That’s why today I wanted to explore a little bit more about psychedelic medicine. For that, I have talked recently to a fascinating person, his name Alexander Bacher, and wanted to see and pick his brain to see what we as parents, or us as individuals who are suffering just in general in life, if there are other ways that we can explore. So let me introduce Alexander. Dr. Bacher is a holistic trauma-informed addiction psychologist. After earning an undergraduate degree at Georgetown and a doctorate in clinical psychology from Pepperdine University, Dr. Bacher went on to work on some of the world’s most renowned addiction treatment centers, including The Kusnacht Practice in Switzerland, Passages in Malibu, Promises in Malibu, and the Betty Ford Center, treating some of the most famous, successful, and powerful people in the world. He specializes in working with dual-diagnosis individuals who struggle with some combination of anxiety, depression, trauma, relationship issues, and addiction. He’s passionate about researching and exploring consciousness, the power of the mind-body relationship, and how to tune into and activate our self-healing potential. He has spent the last 20 years researching the healing potentials of plant medicines and has been fortunate to participate in many indigenous healing ceremonies with master healers, shamans, from North and South America. He also loves traveling and exploring other cultures, their belief systems, and their way of being. He has traveled to 106 countries so far, and plans on visiting all of them before his time’s up. Dr. Bacher provides microdosing coaching services for those looking to come off pharmaceutical medications and discover more natural, healthy ways to heal the mind and the body, as well as those currently struggling with anxiety, stress, and depression, and those who are looking for relief but are worried about taking powerful pharmaceutical drugs which they may have to take for the rest of their lives. Dr. Bacher also provides MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for individuals struggling with acute and chronic trauma who have been unable to find relief from traditional therapy or pharmaceutical medications. He also helps facilitate macrodose psychedelic-assisted therapy sessions utilizing psilocybin for people struggling with addiction, depression, and anxiety, who, again, have been unable to find relief from traditional therapy or pharmaceutical medications. Wow. So I’m excited, Alex. I know we had a fascinating discussion a couple of weeks back, and I thought I’d bring you on. I don’t really have an agenda set out but wanted to reproduce this discussion that we had for our listeners here and see if we can find some answers, or at least maybe have a different perspective on options and opportunities that are out there for all of us that are struggling mentally. So welcome, thank you for your time. Maybe tell us a little bit about your background and how you got interested in psychedelic medicine. I know it’s a hot topic, especially where you are on the West Coast. It’s kind of just still on the kiddie shoes here in Michigan or the rest of the country, I guess, or correct me if I’m wrong. Maybe tell us a little bit about, how did you get to this, and we go from there. Alexander Bacher: Sure. Well, always a pleasure to speak with you, Christian. Thanks so much for having me on your podcast. Really appreciate it. And thank you for that introduction. In terms of my background, I grew up in New York City, and as you had mentioned, I went to Georgetown and was kind of a late bloomer when it came to exploring psychedelics. Actually just attended a global summit conference this past week on psychedelic-assisted therapy and really heard from all the masters and leaders in the field right now, and all of them started off by sharing their experience with psychedelics from early on in their adolescence and 20s. It was interesting to hear their route to where they are today. I noticed early on in college … I was not a big drinker or experimenter in high school, but in college, as I started to have those experiences, I just really shied away from alcohol and never understood why people drank, because I just felt brain dead the next day. It felt like my brain was just- Dr. Bogner: Melting away? Alexander Bacher:… soaking in some toxic environment and couldn’t function or think properly. So I just naturally gravitated towards some of these other psychedelic substances, such as MDMA, psilocybin, and cannabis. And interestingly enough, I wrote my cognitive neuroscience paper at Georgetown back in, I think, 1999 on MDMA and how it affects the brain, because I thought, if I’m going to be experimenting with these molecules, I want to know everything about what they do and how they affect the brain. Of course, there was nowhere near as much research and information back then as there is today, but still was able to find a good amount, and just paid attention to how I felt the day after and the days and weeks after, and recognized that this felt like a much healthier alternative to drinking. Obviously, not using it as frequently, but still. That was my entryway into the personal use of psychedelics. And it continued from there. Again, just becoming fascinated with these non-ordinary states of consciousness and these transpersonal experiences that I and other friends, and colleagues had over the years. Yeah, and that got me interested in exploring more of the research and staying up to date, doing my own research, and again, being invited to participate in these different types of ceremonies with different medicines, I would think, from ayahuasca and San Pedro to toad medicine, which is 5-MeO-DMT, with really well-respected shamans and healers from different parts of Mexico and Peru, and even some Native American chiefs up here in South Dakota. Dr. Bogner: Fascinating, fascinating. Let’s say, for me as a parent with a child with autism, let’s say I have stress. Let’s say there’s depression. Let’s say there are sleep disturbances. It’s understandable. I have a child that’s suffering. How could you live a happy life, really? I don’t think there are many things, or anything, that is potentially worse than having a child suffering day in and day out. Alexander Bacher: Absolutely. Dr. Bogner: We want the best for our children. And that causes problems because you constantly think about, all right, what do I do, what do I do, how do I help my child? I know that our discussion that we had previously was talking about this concept of the default mode network that we have in our brain. Could you elaborate on that, and then maybe also briefly address how is conventional therapy addressing this, and how do psychedelics interact with that system? And what is the purpose in general of this default mode network, and is there a way to free ourselves from that, and what are the consequences? Alexander Bacher: Sure. The default mode network is commonly referred to as the ego part of our brain, which means that it gives us a sense of our separate selves from the world around us. Inherent in that is the idea that everything that we personalize in our waking, conscious experience comes through that part of the brain, or is filtered through that part of the brain. And what we see almost all of the time with anxiety, depression, and other mental illnesses, is overactivity in the default mode network. So that part of the brain is really overactive and just firing more than it should. And with psychedelics, what we find is that it really quiets or turns down the volume on that part of the brain, thereby allowing us to not be subjected to or kind of a slave to it, but rather to connect more fully with other parts of our brain and creativity and just perceptions of reality. So what we find is that when we quiet the default mode network or the ego part of the brain, we’re more able to tune into, again, creativity, and perceptions of reality that we don’t normally notice or take into account. And when we consider that, again, much of mental illness is really unhealthy habits of perceiving, thinking, and behaving, the more we can get out of whatever loop that we’re stuck in terms of the perceiving loop, the thinking loop, the behaving loop, we’re then more able to develop new neural nets or ways of being in the world separate from the conditioned ways that we’re currently. There’s some interesting research that’s been done by Dr. Joe Dispenza, who basically says that we have roughly anywhere from 50 to 70,000 thoughts a day, and out of those 50 to 70,000 thoughts, roughly 90% are the same as e day before and the day before that and the day before that. So we just keep recreating the same reality over and over again, first through our thoughts, then through our actions, then through our behaviors and the resulting feelings, and just this kind of feedback loop. And imagine, just like if you’ve ever seen a cobblestone street and carriage marks that have been weathered over time, the more we get stuck in those loops of perceiving, thinking, behaving, and feeling, they just get ingrained. And there’s some evidence also from Joe Dispenza’s research that by the time we’re 30 years old, about 95% of who we are is this fixed, automatic set of perceptions, thoughts, behaviors, and feelings, just in this loop over and over again. Which begs the question, do we even really have free will, or is it just this illusion of free will that we think we have, where in reality we’ve been conditioned into the state that we are currently, whether that’s a combination of anxiety and stress, depression, rumination? So what we’re finding with these psychedelic medicines, either at a microdose or for sure at a microdose, is they really help snap us out of this rut that we’ve found ourselves in or that we’ve become conditioned to live in. I like to think of it as blinders on, if you ever notice horses that have the blinders on their eyes so they can only see straight ahead, right? So I like to think about how after years and years and years of being a certain way or being conditioned to perceive, think, and behave in a certain way, we have these blinders on. So psychedelics really help just shatter those blinders and help us really perceive reality in a much new and different way than we have before. And what’s interesting is that when that happens and when you have the support of a trained therapist or guide who can help you integrate your experience afterward, it really helps to broaden our perspective, again, on reality and life and how we make sense of it. And with that comes, again, these huge shifts in depression, anxiety, and trauma, such that people, after only sometimes two or three experiences, again, with the trained therapist and with proper integration, are able to really have drastic improvements in depression, anxiety, PTSD, for months if not years into the future. Alexander Bacher: This line, I think, came from … I don’t know if it was Einstein or someone. People often attribute it to Einstein, that quote, but it’s not necessarily true. Again, going back to a lot of the research Dr. Joe Dispenza’s done, which I’m a big fan of his work, is that our brains process roughly 300 billion bits of information per second. And out of that 300 billion bits of information, we’re aware of roughly 0.0000001%, right? Give or take. So I think that’s really more what people are talking about. Most of us are just kind of oblivious to so much of what’s going on internally, in our bodies and in our minds with our thoughts, as well as externally around us. I think a lot of our mental health challenges these days really stem from this disconnection from ourselves and disconnection from the present moment, as well as disconnections from others, communities, and connections around us, such that we’re, again, getting stuck in these patterns of perceiving, thinking, and behaving, and not able to break free from them, which leads to, again, depression, anxiety, rumination, if that makes sense. Dr. Bogner: You mentioned that patients had significant improvement in their lives with just doing three ceremonies. Could you explain that a little bit? And why do you think the changes are persistent? In conventional medicine, we’re trained to believe that, oh, you have depression, you take your Prozac, but you got to take it every day. You better not skip a dose. Why is it that the effects are long-term with an experience like this? The way I understand it is like you’re lost in the jungle, right? You’re panicking, you’re stressed. And what psychedelics can do is to get you on the highest tree in that jungle, and you see, oh, that’s where I have to go. And then you come down, the psychedelics lose their effects, but you remember. Oh, I remember, this is where I have to go. So is it just changing the perception that you have or your outlook, or is it just the experience that you have in general that you’re like, oh my God, there’s so much more out there, that persists? Or what do you think is causing the long-term effects of this? Alexander Bacher: Great question. I’ll speak to two different medicines that are right on the cusp of being FDA-approved, which are MDMA and psilocybin. Let’s start with psilocybin. What we’re finding so far with these medicines is, similar to the way a person can have a really negative, life-threatening experience that causes posttraumatic stress disorder for months or years going forward, so one negative event that really affects them for a long period of time into the future, what we’re finding with, again, psychedelic-assisted therapy, in this case, psilocybin, is that when you have the right setting, the intention, the support of a trained therapist and the proper integration, is that you can have such a profoundly positive, transformational experience that lasts for months or years into the future, causing, again, this radical shift in how you perceive the world. Just some research coming out of Johns Hopkins University, and this is being used with people who have stage 4 cancer and have been given a death sentence in many ways and have end-of-life, death anxiety, so people who are not necessarily in a good head space and have lots to worry about. What they’re finding is that 70% of these people rate their experience with these high doses of psilocybin as one of the five most influential experiences of their lives, on par with things like the birth of their first child or their wedding day. So really powerful experiences, again, that when performed in a safe, contained space with the support of a therapist and proper integration afterward, can really help to take that experience that you’re alluding to like if you’re lost in a jungle and you have this vision or idea of how you can get help and get out … Psychedelics help to, again, get us out of that ego part of the brain and really experience life from a much broader perspective. And sometimes people talk about having this unity experience or this merging with universal energy or love or consciousness, God, or whatever word we want to call it, and just really having the experience that this is just a human body, right? We’re spiritual beings having a human experience, that this human flesh and body is just a temporary form, that the spirit that lies within all of us never dies. It will continue after this body’s gone. So people come out of these, again, only one, two, three experiences, having really profound shifts in consciousness and their views of reality and spirituality, that then tend to stick with them, again, for months or years afterward. So they don’t need to keep having these experiences or taking these medicines over and over again, but it really creates … You know, something just clicks. And what we find is that people just naturally want to start living more healthy lives. It’s been found to be really helpful for addiction as well, even back in the ’50s. Most people don’t know this. Over a thousand research studies were done back in the ’50s related to addiction to LSD, with incredible results. Even Bill W., the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, most people don’t know that he got sober after years of trying numerous different things. It was only after an LSD experience that really helped create that shift in his perspective, consciousness, and something clicked where he got sober and never went back to drinking. We see this, again, with trauma, addiction, anxiety, and depression, that something just shifts internally. People just naturally want to start living more healthy, active lives, giving up drinking, eating more healthily, and exercising more. It’s really interesting. So that’s psilocybin. When it comes to MDMA, MDMA is actually going to be most likely the first psychedelic medicine that’s approved by the FDA, hopefully later this year, 2023, or early 2024. But I want to be clear, it’s MDMA with MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. So it’s not just the MDMA itself, right? I don’t want people to get confused or think that, oh, they should just go out and have MDMA experiences on their own. It’s really MDMA with this inner-directed therapy. The research on this is truly amazing. The research is taking folks who most of them have … I think the average number of years with severe PTSD was 14 years, and a third of the people, a third of the study participants had severe PTSD for over 20 years. So we’re talking really long-term trauma, trying everything that is out there, all different medications, various types of therapy. Nothing’s working. Highly suicidal. Many of them never felt like they had a safe person or had a felt sense of love in their life. And what they found is that almost 70% of these folks, within two or three MDMA-assisted psychotherapy sessions, followed by three or four integration sessions each time, about 70% of them had their PTSD completely disappear, and another 28% of them had clinically significant declines in the PTSD symptoms, for months and sometimes years afterward. I mean, truly mind-blowing results, such that the FDA has granted breakthrough status to MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, which is really helping to push it through now hopefully later this year to make it approved. So what we’re finding here is that a lot of trauma … Actually, trauma, as described by … I think Dr. Gabor Mate explained it this way. Trauma is not what happened to us. It’s what happens inside of us. What that means is that it’s how we interpret or make sense of those events that happen in our lives. And so much trauma comes from early attachment issues. Again, and it’s not what was done to us, but it’s almost what didn’t happen to us, that we didn’t have the emotional support, understanding of what we were going through, upsetting events where we were neglected. So MDMA is this really special molecule. There’s really no other drug or medicine like it, where it’s an immediate-acting anti-anxiety as well as an immediate-acting stimulant that also stimulates oxytocin and prolactin in the brain, which are the bonding chemicals that mothers and infants secrete when they’re breastfeeding or they have skin-to-skin contact from bonding or cuddling. So MDMA really gives people this felt a sense of love and acceptance and empathy, sometimes for the first time ever in their lives. MDMA is also known as ecstasy. That’s its street name. And it’s also nicknamed the love drug, right? So really, people are being wrapped in this warm blanket of love, unconditional love, and acceptance for themselves, and for others. And what we find is that … It’s really another interesting statistic, is that about 80% of people, when they were doing MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, started to do what’s called parts work on their own. A lot of times, we cut off different parts of ourselves that are unwanted or we think are bad, the part of us that gets really angry or upset or frustrated, that we try to push them aside and be the nice person that we’re supposed to be. What we find with MDMA-assisted psychotherapy is that people naturally start to do parts work, where they start to integrate various parts of themselves that have been unwanted or cut off, and we bring them back into ourselves and help integrate them in a healthy way, helping to make ourselves whole and heal ourselves. It’s similar to … If you get a cut on your body, you don’t have to tell your body how to heal itself, right? You just clean the cut and put a bandaid over it, and the cut will heal itself. What we’re finding is that the same thing seems to work from a mental health standpoint when we create the right conditions for healing. So if we create, again, the safe space, the safe container, the support of a therapist, with these medicines like MDMA, it’s almost like we’re allowing the person this inner-directed healing to heal him or herself from the inside out, with, again, the right setting and support. It’s really interesting. Dr. Bogner: Wow… It’s almost like setting off this cascade of events, almost setting the spark with this to heal thyself, right? Alexander Bacher: Absolutely. Dr. Bogner: Tell me about this conundrum. I’m going to my doctor, and within 15 minutes, he diagnoses me with depression. I’m not talking personally, I’m talking general. It happens every day in every office of a family physician. And he prescribes Prozac. We know Prozac’s FDA-approved for depression, but when you look at the side effects, insomnia, headache, drowsiness, anxiety, nervousness, sexual problems, weight gain, and the ultimate, suicide, black box warning, right? So we know that psilocybin … And by the way, for those that don’t know, psilocybin also known as magic mushrooms, has certainly been around for, I think, thousands of years, you told me, much longer than Prozac. But we know that from these medications, you cannot die. Just like we know from cannabis, you can’t die. You can eat a pound of it and you will be pretty high, but you won’t die. The same with LSD, with psilocybin. Not sure about MDMA. But the FDA considers it a Schedule I, highly illegal. So why is that the case? What is their reasoning in regards to justifying that this is a Schedule I drug, and where are we with this? You mentioned Johns Hopkins, and I’m sure a lot of other big universities are studying this, maybe even worldwide. I know in England they’re doing a lot of research on psychedelics. But where are we with this, and what can we expect over the years? If there’s a trial coming out showing benefits, why wouldn’t it be scheduled? And how are you integrating this into your practice? How’s that possible? How can you do this? How can I do this here in Michigan, for example? Just a general moment in time, where are we with this? Alexander Bacher: Sure, great question. Let me see if I can cover all of it. If I leave anything out, remind me. But it’s really almost laughable that three out of the four Schedule I substances are MDMA, psilocybin, LSD, actually cannabis, and then heroin. So four out of the five of them. Dr. Bogner: Isn’t DMT… DMT, isn’t that on the list too? Dimethyltryptamine? Alexander Bacher: Possibly. I’m not sure. It probably is. But how all these … And cocaine is actually a Schedule II substance. I mean, it’s really ridiculous. In my mind, alcohol should be a Schedule I substance if we’re going to go really by harmful, no medical benefits, and what it does to the body. So it’s kind of interesting how now MDMA, psilocybin, cannabis, all these, and hopefully soon as well LSD, we’re realizing that they actually do have immense health benefits when it comes to helping with mental health treatment and care. Unfortunately, all these substances were listed back in 1970 with the Controlled Substances Act as Schedule I substances, because partly they got caught up in the whole hysteria of the antiwar movement and the hippie movement, and Nixon trying- Dr. Bogner: Richard Nixon? Alexander Bacher: Yeah, and Richard Nixon trying to paint the antiwar movement as a bunch of people doing drugs, and discrediting them and making them into these drug-using offenses, which is ridiculous because what we’re finding is that unlike the fact that alcohol makes people aggressive … Right? I think something like 70% of people who are arrested for assault are intoxicated by alcohol. Psychedelics actually make much better citizens, right? Psychedelics actually reduce violent crime. They reduce partner violence. They create a sense of interconnectedness, looking at yourself within a larger context of a whole, not being separate and alone in the world, but seeing yourself as part of a larger whole. So there’s so many that we’re finding, wow, again, such that FDA has now granted breakthrough status to two of them. And hopefully, LSD will be coming along soon after. But unfortunately, because there’s been so much misinformation and lies spread about LSD, and also what the CIA did, just testing it for mind control on people back in the ’50s and ’60s without them knowing, there’s a dark history there. So unfortunately it’s been slower to come along. But other countries, like Switzerland, are, thank God, doing studies with LSD which are showing very promising results as well. But back to your question about how can we access them now, or what’s the current state, and how can people start to work with it. You mentioned the fact that, yes, when it comes to depression right now, you go to any psychiatrist, their first line of defense, it, unfortunately, is, yes, considering medication. Because most psychiatrists, especially the ones that are trained in the last 20 years, aren’t taught … They’re not given any other tools except, here’s your pill, here’s your antidepressant, here’s your antianxiety, here’s your antipsychotic. They’re so limited in their ability to treat mental health issues. And the irony is that when it comes to … The only legal substance these days is ketamine that’s been FDA-approved. So when it comes to even recommending ketamine, they first have to go through every other medication available first and find out if all of those don’t work, and then they can go with ketamine, which to me is just the pharmaceutical lobbies pushing their drugs onto people, right? Because it’s like, why should we go through all these other ones when similar to MDMA and psilocybin, we’re finding huge results with ketamine, Dr. Bogner: And not only them, but practitioners. Alexander Bacher: Oh, yeah. The whole psychiatry. If I were a psychiatrist, I would be terrified, because my whole career is threatened at this point, unless the ones who are already starting to embrace it. But I can’t even find it, for the most part … Most of my friends, and colleagues who are psychiatrists don’t know much about psychedelics. And when I look to partner with people … because I get so many people who come to me who say, “Listen, I’m tired,” like you were saying, “of being on this antidepressant, anti-anxiety medication, where I become like a slave to it. I’m addicted to it, I can’t get off it, or I have serious side effects, sexual side effects, or what have you. Or that it’s no longer working for me, and now I got to switch to a new antidepressant, and when I come down off it, I’m suicidal, I’m just unable to function and work.” It’s unbelievable to hear how hard it is for people to get off these medications once they’re on them for a long period of time. And the vast majority, once they are started on them, end up getting stuck on them for years. Then by then, it’s so hard to get off and transition. And then you’re dealing with side effects of other medications [inaudible 00:39:57] to help with the one that you’re trying to get off of. Dr. Bogner: Yeah, explain to us the micro-dosing, macro-dosing. I would assume when you talk about the ceremonies, we are talking about macro dosing, so more like a supervised bigger dose, supervised. But what about micro-dosing? That’s more a non-supervised, kind of my morning routine, using a small amount. Alexander Bacher: Yeah, micro-dosing is usually taking one-tenth of a normal standard dose or less. And you want to figure out what the sweet spot is for you. But it’s taking one-tenth of a dose or less for a period of time, for like one to three months. And there are different types of protocols. There’s the Dr. Fadiman protocol, which is one day on, two days off, and then there’s the Paul Stamets protocol, which is five days on, two days off. But ideally, you want to work with someone like myself or someone who’s a microdose coach or has some experience with these different types of medicines and knows which one would be better for whatever it is you’re looking for. But once we figure out which one makes the most sense for whatever your needs are, yeah, you’re basically taking the dose, whether it’s one day on, two days off, or five days on, two days off, for a period of time, and just journaling, just paying attention to what you’re noticing. And a lot of times, microdoses are sub-perceptual, right? This means that oftentimes you don’t even notice what’s going on. Some people describe it as, it’s not what you notice but what you don’t notice. So you don’t notice the anxiety, or you don’t notice the depression, you don’t notice the rumination. So it’s, again, these subtle effects on the default mode network like we were talking about before, where even with the microdose level, it really helps to quiet or turn down the volume on that ego part of our brain so that we’re not ruminating, we’re not stressed out or anxious, or ruminating, depressed, where we’re able to just turn down the volume and focus more on creativity and being in the present moment and coming up with new ideas for whatever our work or our career is. And what we find also is that, again, even with the microdose, it helps to naturally motivate people to start living more healthy lives. So even at microdoses for one, two, three months, then we ask people to pause and just see how things are going, because usually during that one to three months, people start to develop more healthy routines and activities, like eating more healthy, not drinking as much, starting to hike or go a gym or frequently or do more yoga. It takes about 90 days for a behavior to become automatic, a part of ourselves. So what we find is that after, again, one, two, three months of microdosing, people start to develop these more healthy habits of thinking, of behaving, and perceiving, that when we have them stop, they continue with these newly developed habits and continue living these more healthy ways and not experience as much, again, anxiety, stress, depression, and rumination. Dr. Bogner: Okay, okay. Alex, for those of us who want to find out more about how to get started with this, obviously, because it is a Schedule I, I’m not advocating anyone trying this, obviously, without discussing this with your healthcare providers, but let’s say somebody wants to take that next step and says, “All right, I want to talk more on a personal level, discuss my issues, and see what plan we can generate from here,” how can they get in contact with you? And do you even provide services like that for individuals in regards to counseling? How does that work? Alexander Bacher: Yes. Again, let’s reiterate and be very clear that these medicines are still Schedule I illegal drugs, according to the DEA. I do work with people, but I don’t provide the medicines to them. However, that being said, it’s similar to the way a psychiatrist works with the pharmacy. I do work with people who are very reputable producers and distributors of these medicines. So once I meet with a person and determine whether it’s a good fit for us to work together and to do microdose coaching or psychedelic-assisted therapy, I will then refer the person to these producers, and distributors, to obtain the medicine in the correct dose, and then work with the client in that way as a way to protect myself, but also to help people to get access to these medications which, again, are just really game-changers when it comes to mental healthcare. And the way people can connect with me, you can just Google my name, Dr. Alexander Bacher, which is B-A-C-H-E-R. I have a website, conciergeaddictiontreatment.com. I also wrote a book called Being Human: Reclaiming Our True Power and Potential, and I have a website for that book as well. It’s called beinghumanmovement.com. You can also follow me on Instagram, DrAlexanderBacher. I post a lot of information there helping to educate people related to microdosing and just how awful the current state of affairs of our Western medical approach to treating mental illness is, through medication and through symptom suppression as opposed to getting to the root cause and helping to create healing from within. Dr. Bogner: Fascinating. Well, thank you so much, Alex. I appreciate your time. Hopefully, I can have you back on this podcast to dive maybe a little bit deeper into it. And yeah, thanks. Anyone who’s interested, please contact Alex. Hopefully, it will help you. Have a great day in California, Alex. Alexander Bacher: Thanks so much. You too, Christian. All the best. Take care.

It’s not about what you notice, but what you don’t notice.

Transcripts (in PDF)English / Arabic / Chinese / Bulgarian / Russian / German / French / Hindi / Spanish

Dr. Alexander Bacher – Concierge Addiction Treatment – Los Angeles

Dr. Bogner: Wow. The way I understand it, the way you’ve explained it, it’s not only that we have to have a previous trauma, for example, of PTSD, or current depression or anxiety or stress, but it’s the other way around too, that our just everyday life, our conditioned life, just going to work, drinking our coffee, watching our Netflix, that that repetitive behavior is looping us into this default mode network that leads to eventual depression and anxiety because this default mode network is putting the blinders on from us connecting to the outside world. Is this why you believe that … I don’t know if it’s true, but I think it is, that we only use 10% of our brain and all this other untapped potential we’re shielded from because of this conditioned, every day the same thinking? As you mentioned, 90% of the thoughts that I have today, I had yesterday. Is that part of the reason, you believe?

which you don’t need to take for the rest of your life or every day? You just have to have a couple of ketamine-assisted therapy sessions, and we see massive changes and shifts that last for a period of time. Sometimes you need to come back for some more in six to eight weeks, or a couple more, but not on a daily basis, right? And to me, I think the pharmaceutical lobby is terrified by what’s coming down the road with these medicines, because yeah- I work with people that are from a micro dosing standpoint, and there’s literally no harm that can come from microdosing LSD and psilocybin. These are completely natural, nontoxic substances. Not that I want to encourage high doses of LSD, because there’s a whole different beast, but there’s no known toxic dosage of LSD that even exists on a neurotoxicity level. But let’s talk about microdoses.

I work with people that are from a micro dosing standpoint, and there’s literally no harm that can come from microdosing LSD and psilocybin. These are completely natural, nontoxic substances. Not that I want to encourage high doses of LSD, because there’s a whole different beast, but there’s no known toxic dosage of LSD that even exists on a neurotoxicity level. But let’s talk about microdoses.